Tariffs, Trade and Taxes in the Time of Trump

In Short

By Michael Mix,

Managing Director and Portfolio Manager at Conning

“Tariff” is a term closely associated with President Donald Trump, but the history of tariffs in the U.S. economy dates back to the days of George Washington. And while the tariff trail is easy to track, what is far less clear is how the 47th president will apply this long-time trade tool and its potential impact.

Tariffs were a significant source of federal revenue through the early 20th century but eventually proved insufficient to fund the modern U.S. government; personal and corporate taxes now carry most of the burden.

Trump appears to think that, like President McKinley in the late 1890s, tariffs can be ramped up to drive significant federal revenue and generate economic growth. Others think that in today’s far more global economy Trump’s plans will lead to inflation, beggar-thy-neighbor tariff retaliation from U.S. trading partners, international animosity and a weaker U.S. economy.

As tariffs are under greater consideration, Conning examines their historical significance and explores potential implications of new tariff measures.

A Historical Revenue Source

Congress authorized the federal government to levy taxes and tariffs in 1789, and that year President Washington signed the “Tariff of 1789” bill that imposed a tariff of about 5% on nearly all imported goods.

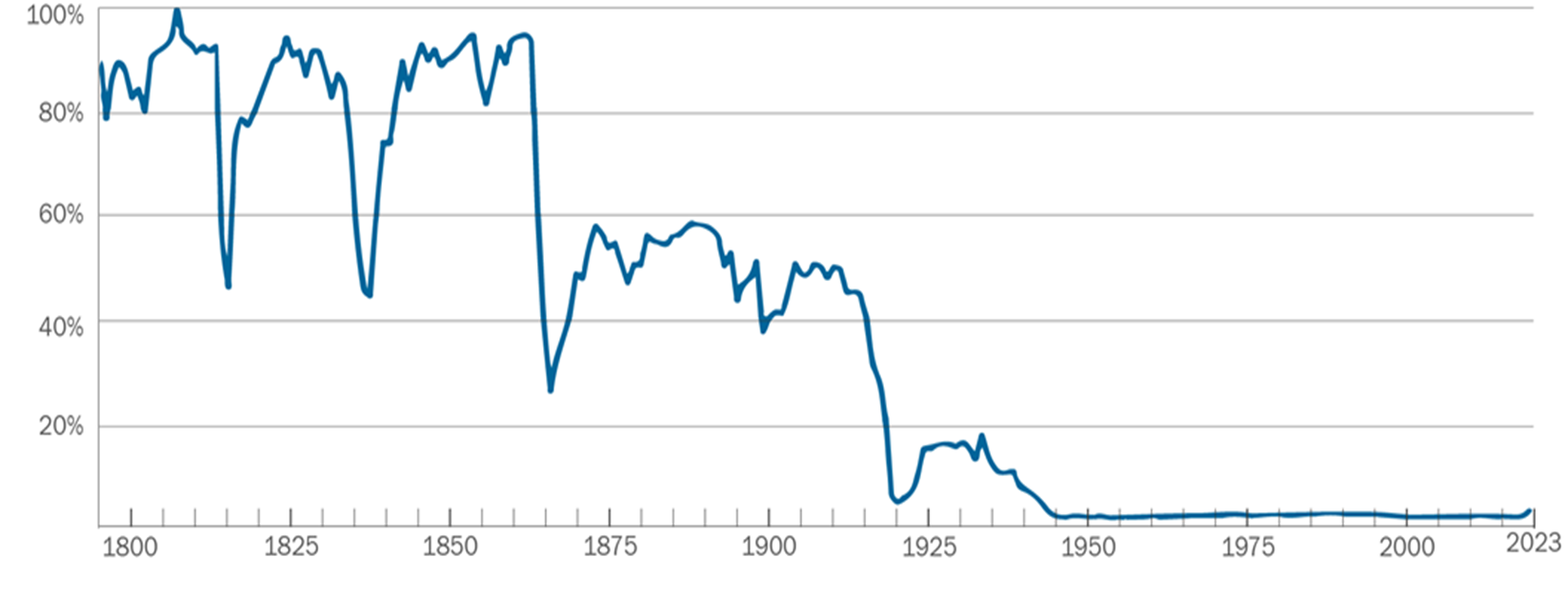

Figure 1 - Tariffs Revenue as a Share of Total Federal Receipts, 1798-2023

Prepared by Conning, Inc. Source: “Tariffs as a Major Revenue Source: Implications for Distribution and Growth,” The White House Counsel of Economic Advisors Blog, July 12, 2024, https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/cea/written-materials/2024/07/12/tariffs-as-a-major-revenue-source-implications-for-distribution-and-growth/

Tariffs were a good fit for our then mostly agrarian economy in which individual income was harder to measure than goods being offloaded at ports. By 1860, tariff revenues accounted for over 90% of federal revenues (see Figure 1).

However, a growing U.S. government required more revenue, and as ever-higher tariffs reduced imports, an income tax was seen as a way to broaden the payer base and force higher-income individuals to pay a larger share of government expenses. A 1913 constitutional amendment created the U.S. income tax and the Underwood Tariff Act of that year lowered tariff rates from about 40% to 25%. Tariff revenues dropped sharply and by 1920 accounted for approximately 5% of federal revenues (also illustrated in Figure 1).

Other than an increase in tariff rates to nearly 60% in 1930 (the Smoot-Hawley Tariffs were believed to have contributed to the depth of the Great Depression), tariff revenues have been on the decline. Despite the attention tariffs received during Trump’s first term, income taxes remained the primary source of all federal revenues; tariff revenues made up less than 2%.

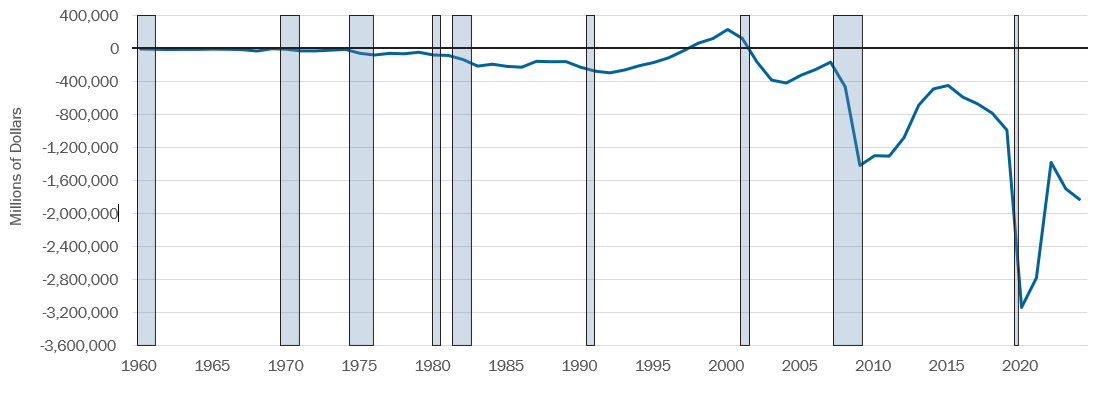

However, in recent years, income taxes have been insufficient to cover government spending. Other than a short period between 1998 and 2001, the U.S. government has run consistent budget deficits since the mid-1970s. The deficits were particularly acute after 2007 (see Figure 2) when federal funding to support the impact of the Great Financial Crisis in 2007-2008 and in 2020 to support the Covid pandemic. Funding those deficits has led to a massive amount of debt issuance, which as of March 6, 2025, reached $36.22 trillion.1

Figure 2 - Federal Surplus or Deficit [-], 1960-2024 Q3

Shaded areas indicate U.S. recessions.

Prepared by Conning, Inc. Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Federal Surplus or Deficit 2000-2024, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYFSD, as of March 17, 2025

Easier to Raise Tariffs than Taxes

Are U.S. tax rates too low? The current highest marginal tax bracket remains in the middle of its historic range (see Figure 3). Some economists suggest that lower tax rates provide a stimulative effect, thereby increasing growth and eventually generating higher levels of income tax receipts; a tax increase, they note, might have a negative effect.

The political will to raise taxes may have died with George H. W. Bush’s “Read my lips, no new taxes” flipflop in 1990. Trump himself will have work to do with Congress this year to maintain the tax decreases that were in his 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which are due to expire at the end of the year. If he fails, he will own the tax “increase” as rates revert to higher pre-TCJA levels.

Further, Trump believes that the structure of the tariff system is what is broken, rather than a function of Americans not paying enough. A recent fact sheet put out by his administration argues that non-reciprocal tariffs, where America’s trading partners charge U.S. goods a higher tariff than the U.S. government charges on foreign goods, encompass 132 countries and more than 600,000 product lines and cause U.S. exporters to face higher tariffs more than two-thirds of the time. The same fact sheet points out that non-reciprocal foreign taxes levied on U.S. companies (such as the ‘digital service tax’ charged by Canada and France), cost American firms over $2 billion per year.2 In the eyes of the administration, the reciprocal approach to tariffs and taxes would either force a reduction in those costs to U.S. companies or, if matched, create a new source of revenue for the U.S. government.

Drive Inflation – or Growth?

A tariff on an imported good raises its price; importers can either absorb the cost or pass it on to the consumer. At least in the short term, the consumer will likely end up paying some of the tariff which would be an inflationary effect.

However, tariffs should not be viewed in isolation. The elasticity of demand and availability of substitutes for a particular good will ultimately influence the result. Currency effects matter as well: over the long term, as tariffs slow the flow of imports into the U.S., the demand for foreign currency to pay for those goods is reduced and the foreign currency will depreciate versus the dollar (i.e., the dollar strengthens relative to that currency which provides a deflationary effect that acts to cancel the inflationary effect of the tariff). Central bank interventions may also have an impact: if the U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed) responds to slowing U.S. growth that may be due to tariffs by increasing the money supply (i.e., monetary accommodation), that would likely be inflationary, but that would be Fed-driven inflation rather than tariff-driven inflation.

Trump believes that raising tariffs will create growth. If tariffed goods cost more, U.S. manufacturers should be encouraged to expand production of those same goods and sell them at lower prices. International producers might also establish U.S.-domiciled operations to do the same. There is historical precedent: in the late-1980s, Toyota established U.S. production facilities to avoid the 25% retaliatory “Chicken Tax” placed on U.S. light-truck imports by President Johnson in 1964.3 Other foreign vehicle manufacturers followed.

Trump believes this expansion of domestic operations would enlarge the workforce, lift wages and help consumers deal with the higher prices experienced in recent years. Vice President J.D. Vance added that, if the U.S. could utilize cleaner manufacturing methods, the expansion of the industrial base could also take growth from other countries that are polluters.

Time is likely the enemy of such thoughts. There is also a delicate balance between a rise in prices of imported goods and the impact on the domestic economy. If prices rise too quickly, the economy could stumble. Second, short-term shifts in consumption don’t normally motivate capital allocators and would unlikely be enough to spur foreign companies to make significant investments in the U.S. Add to that the fact that Trump is now term-limited, with no guarantees that a subsequent administration won’t reverse course on tariff policy, and the time runway gets shorter.

Will Countries Retaliate?

During Trump’s first term, while tariffs were imposed on several countries, the primary focus was clearly on China. China appeared less concerned with the U.S. tariffs at first, then enacted its own tariff regiments in retaliation. As a net exporter to the U.S., the retaliation was less effective than that of the U.S. tariffs and the lack of U.S. company access into China’s economy also likely blunted the effect.

There are competing views about the true impact of tariffs on the global economy, largely begun in mid-2018, and likely influenced by the Covid event in early-2020. However, it is important to note that the U.S. and China are still living with the tariffs that were enacted by both sides. In fact, the Biden administration kept all of the U.S.’s Trump-era tariffs in place and added a few of its own.

If the U.S. introduces a new series of tariffs, retaliation by China could take a different approach this time, with retaliatory tariffs or even other defensive measures. For example, the U.S. could see a pronounced rise in the level of cybercrime, a tactic at which the Chinese Communist Party has shown to be particularly adept,4 or the U.S. could be further limited in accessing China’s rare earth minerals.

As the tariff threat seems to be directed to several more countries (including large trading partners Mexico, Canada and Europe), some countries may decide to band together in a NATO-like manner so that any tariff against one country would be viewed as a move against all countries in the block and they would be required to respond with their own tariffs against the U.S.

"In general, investors don’t deal well with uncertainty, proving more willing to sell first and ask questions later. A sharp downturn in global markets could produce the opposite impact that Trump seeks."

Tariffs as a Global Policy Tool

Tariffs are also a tool for enforcing U.S. foreign policy and Trump has not been shy about expressing his views of using tariffs to manage international relationships – again, even with our largest trading partners.

He has used tariff threats against Canada and Mexico to change how those countries allow migrant passage into the U.S. China is also a target given the nation’s military ambitions and intellectual property theft by Chinese companies.5 And let’s not forget the sanctions (i.e. the ultimate form of tariff) that the U.S. placed on Russia at the start of the war in Ukraine.

In a world of fewer military battles, economic battles have become more prevalent and tariffs have become a highly visible and effective tool.

Investment Implications

Forecasting economic growth is always a challenge even when you have all the facts; the extent and timing of Trump’s tariffs are unknown.

The administration had several fits and starts with tariffs in early 2025; announcing the enactment of tariffs only to delay and/ or amend the terms. At this point, what seems to be sticking is a focus on China with a 20% (initial 10% then an additional 10%) tariff on all goods, a 25% tariff on global steel and aluminum imports into the U.S. and a 25% tariff on goods from Canada and Mexico (with carve-outs for automakers and specific products). The administration is due to release its plan for reciprocal tariffs on all U.S. trade partners on April 2. Tariffed countries have announced their own retaliatory tariffs and have sparred with Trump with their own threats.

Conning will keep up with the headlines but also keep an eye on the economic data for clues as to how tariffs are affecting the U.S. and global economy. We believe that tariffs will likely hit the consumer first so we would track that segment closely for signs of stress. We think the weekly jobless claims and monthly employment reports will likely offer the first glimpses of impact, along with monthly advanced retail sales data.

Inflation will also be an important metric to track. Any uptick could cause the Fed to raise short-term interest rates and that could push up long-term rates. Higher rates can provide opportunities to add yield and subsequentially income to portfolios, but we are mindful that inflationary effects will eventually strain corporate financiers and credit issues, possibly breaking what we have seen as a prolonged period of benign credit events.

Short of outright retaliation, we also need to be concerned about the impact of the perception and confidence of global consumers and the effect on global markets. In general, investors don’t deal well with uncertainty, proving more willing to sell first and ask questions later. A sharp downturn in global markets could produce the opposite impact that Trump seeks.

About Conning

Conning (www.conning.com) is a leading investment management firm with a long history of serving insurance companies and other institutional investors. Conning supports clients with investment solutions, risk modeling software, and industry research. Founded in 1912, Conning has investment centers in Asia, Europe and North America. Conning is part of the Generali Group.

Legal Disclaimer

©2025 Conning, Inc. Conning, Inc., Goodwin Capital Advisers, Inc., Conning Investment Products, Inc., a FINRA-registered broker-dealer, Conning Asset Management Limited, and Conning Asia Pacific Limited (collectively “Conning”) and Octagon Credit Investors, LLC, Global Evolution Holding ApS and its subsidiaries, and Pearlmark Real Estate, L.L.C. and its subsidiaries (collectively “Affiliates” and together with Conning, “Conning & Af- filiates”) are all direct or indirect subsidiaries of Conning Holdings Limited which is one of the family of companies whose controlling shareholder is Generali Investments Holding S.p.A. (“GIH”) a company headquartered in Italy. Assicurazioni Generali S.p.A. is the ultimate controlling parent of all GIH subsidiaries. This document and the software described within are copyrighted with all rights reserved. No part of this document may be distributed, reproduced, transcribed, transmitted, stored in an electronic retrieval system, or translated into any language in any form by any means without the prior written permission of Conning & Affiliates. Conning & Affiliates do not make any warranties, express or implied, in this document. In no event shall any Conning & Affiliates company be liable for damages of any kind arising out of the use of this document or the information contained within it. This document is not intended to be complete, and we do not guarantee its accuracy. Any opinion expressed in this document is subject to change at any time without notice.

This document is for informational purposes only and should not be interpreted as an offer to sell, or a solicitation or recommendation of an offer to buy any security, product or service, or retain Conning & Affiliates for investment advisory services. The information in this document is not intended to be nor should it be used as investment advice.

Copyright 1990-2025 Conning, Inc. All rights reserved.

Footnotes

1 Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service, Dataset Search, Debt to the Penny, accessed March 6, 2025, https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/datasets/debt-to-the-penny/debt-to-the-penny

3 Source: Tax Policy Center, Urban Institute and Brookings Institution, “Does the ‘Chicken Tax’ encourage people to purchase larger trucks?”, Robert McClelland, May 31, 2023, https://taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/does-chicken-tax-encourage-people-purchase-larger-trucks

4 Source: U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, “The Threat Posed by the Chinese Government and the Chinese Communist Party to the Economic and National Security of the United States”, Remarks of Director Christopher Wray at Hudson Institute Event: China’s Attempt to Influence U.S. In- stitutions, Washington, D.C., July 7, 2020, https://www.fbi.gov/news/speeches/the-threat-posed-by-the-chinese-government-and-the-chinese- communist-party-to-the-economic-and-national-security-of-the-united-states

5 Ibid

Additional Disclosure

This viewpoint is published by Conning, Inc. (“Conning”) and represents the opinion of Conning. It may not be reproduced or disseminated in any form without the express permission of Conning. This publication is intended only to inform readers about general developments of interest and does not constitute investment advice or a solicitation. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained herein, Conning does not guarantee such accuracy and cannot be held liable for any errors in or any reliance upon this information. Conning does not guarantee that this publication is complete. Opinions expressed herein are subject to change without notice.

COD00001009